– Geology, Geography, Human Geography, Physical Geography, Social Studies, World History

Culled from National Geographic

Africa is sometimes nicknamed the “Mother Continent” due to its being the oldest inhabited continent on Earth. Humans and human ancestors have lived in Africa for more than 5 million years.

Africa, the second-largest continent, is bounded by the Mediterranean Sea, the Red Sea, the Indian Ocean, and the Atlantic Ocean. It is divided in half almost equally by the Equator. The continent includes the islands of Cape Verde, Madagascar, Mauritius, Seychelles, and Comoros.

Africa’s physical geography, environment and resources, and human geography can be considered separately.

The origin of the name “Africa” is greatly disputed by scholars. Most believe it stems from words used by the Phoenicians, Greeks, and Romans. Important words include the Egyptian word Afru-ika, meaning “Motherland”; the Greek word aphrike, meaning “without cold”; and the Latin word aprica, meaning “sunny.”

Today, Africa is home to more countries than any other continent in the world. These countries are: Morocco, Western Sahara (Morocco), Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Egypt, Sudan, Chad, Niger, Mali, Mauritania, Senegal, The Gambia, Guinea-Bissau, Guinea, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Burkina Faso, Togo, Benin, Nigeria, Cameroon, Central Africa Republic, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Congo, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Angola, Namibia, Botswana, South Africa, Lesotho, Swaziland, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Zambia, Malawi, Tanzania, Rwanda, Burundi, Uganda, Kenya, Somalia, Ethiopia, Djibouti, Eritrea and the island countries of Cape Verde, Madagascar, Mauritius, Seychelles, and Comoros.

Cultural Geography

Historic Cultures

The African continent has a unique place in human history. Widely believed to be the “cradle of humankind,” Africa is the only continent with fossil evidence of human beings (Homo sapiens) and their ancestors through each key stage of their evolution. These include the Australopithecines, our earliest ancestors; Homo habilis, our tool-making ancestors; and Homo erectus, a more robust and advanced relative to Homo habilis that was able to walk upright.

These ancestors were the first to develop stone tools, to move out of trees and walk upright, and, most importantly, to explore and migrate. While fossils of Australopithecines and Homo habilis have only been found in Africa, examples of Homo erectus have been found in the Far East, and their tools have been excavated throughout Asia and Europe. This evidence supports the idea that the species of Homo erectus that originated in Africa was the first to successfully migrate and populate the rest of the world.

This human movement, or migration, plays a key role in the cultural landscape of Africa. Geographers are especially interested in migration as it relates to the way goods, services, social and cultural practices, and knowledge are spread throughout the world.

Two other migration patterns, the Bantu Migration and the African slave trade, help define the cultural geography of the continent.

The Bantu Migration was a massive migration of people across Africa about 2,000 years ago. The Bantu Migration is the most important human migration to have occurred since the first human ancestors left Africa more than a million years ago. Lasting for 1,500 years, the Bantu Migration involved the movement of people whose language belonged to the Kongo-Niger language group. The common Kongo-Niger word for human being is bantu.

The Bantu Migration was a southeastern movement. Historians do not agree on why Bantu-speaking people moved away from their homes in West Africa’s Niger Delta Basin. They first moved southeast, through the rain forests of Central Africa. Eventually, they migrated to the savannas of the southeastern and southwestern parts of the continent, including what is today Angola and Zambia.

The Bantu Migration had an enormous impact on Africa’s economic, cultural, and political practices. Bantu migrants introduced many new skills into the communities they interacted with, including sophisticated farming and industry. These skills included growing crops and forging tools and weapons from metal.

These skills allowed Africans to cultivate new areas of land that had a wide variety of physical and climatic features. Many hunter-gatherer communities were assimilated, or adopted, into the more technologically advanced Bantu culture. In turn, Bantu people adopted skills from the communities they encountered, including animal husbandry, or raising animals for food.

This exchange of skills and ideas greatly advanced Africa’s cultural landscape, especially in the eastern, central, and southern regions of the continent. Today, most of the population living in these regions is descended from Bantu migrants or from mixed Bantu-indigenous origins.

The third massive human migration in Africa was the African slave trade. Between the 15th and 19th centuries, more than 15 million Africans were transported across the Atlantic Ocean to be sold as slaves in North and South America. Millions of slaves were also transported within the continent, usually from Central Africa and Madagascar to North Africa and the European colony of South Africa.

Millions of Africans died in the slave trade. Most slaves were taken from the isolated interior of the continent. They were sold in the urban areas on the West African coast. Thousands died in the brutal process of their capture, and thousands more died on the forced migration to trading centers. Even more lost their lives on the treacherous voyage across the Atlantic Ocean.

The impacts of slavery on Africa are widespread and diverse. Computerized calculations have projected that if there had been no slave trade, the population of Africa would have been 50 million instead of 25 million in 1850. Evidence also suggests that the slave trade contributed to the long-term colonization and exploitation of Africa. Communities and infrastructure were so damaged by the slave trade that they could not be rebuilt and strengthened before the arrival of European colonizers in the 19th century.

While Africans suffered greatly during the slave trade, their influence on the rest of the world expanded. Slave populations in North and South America made tremendous economic, political, and cultural contributions to the societies that enslaved them. The standard of living in North and South America—built on agriculture, industry, communication, and transportation—would be much lower if it weren’t for the hard, forced labor of African slaves. Furthermore, many of the Western Hemisphere’s cultural practices, especially in music, food, and religion, are a hybrid of African and local customs.

Contemporary Cultures

Contemporary Africa is incredibly diverse, incorporating hundreds of native languages and indigenous groups. The majority of these groups blend traditional customs and beliefs with modern societal practices and conveniences. Three groups that demonstrate this are the Maasai, Tuareg, and Bambuti.

Maasai peoples are the original settlers of southern Kenya and northern Tanzania. The Maasai are nomadic pasturalists. Nomadic pastoralists are people who continually move in order to find fresh grasslands or pastures for their livestock. The Maasai migrate throughout East Africa and survive off the meat, blood, and milk of their cattle.

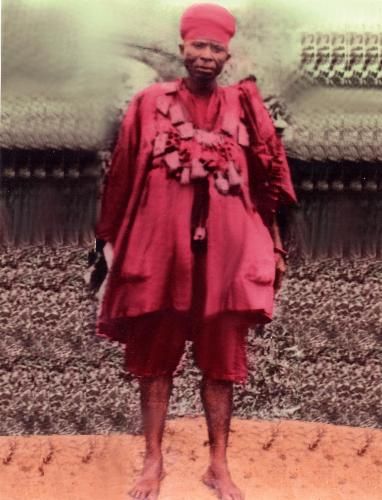

The Maasai are famous for their striking red robes and rich traditional culture. Young Maasai men between the ages of 15 and 30 are known as moran, or “warriors.” Moran live in isolation in unpopulated wilderness areas, called “the bush.” During their time as moran, young Maasai men learn tribal customs and develop strength, courage, and endurance.

Even though some remain nomadic, many Maasai have begun to integrate themselves into the societies of Kenya and Tanzania. Modern ranching and wheat cultivation are becoming common. Maasai also support more tribal control of water resources. Women are pressuring the tribe for greater civil rights, as the Maasai is one of the most male-dominated societies in the world.

The Tuareg are a pastoralist society in North and West Africa. The harsh climate of the Sahara and the Sahel has influenced Tuareg culture for centuries.

Traditional Tuareg clothing serves historical and environmental purposes. Head wraps called cheches protect the Tuareg from the Saharan sun and help conserve body fluids by limiting sweat. Tuareg men also cover their face with the cheche as a formality when meeting someone for the first time. Conversation can only become informal when the more powerful man uncovers his mouth and chin.

Light, sturdy gowns called bubus allow for cool airflow while deflecting heat and sand. Tuaregs are often called the “blue men of the Sahara” for the blue-colored bubus they wear in the presence of women, strangers, and in-laws.

The Tuareg have updated these traditional garments, bringing in modern color combinations and pairing them with custom sandals and silver jewelry they make by hand. These updated styles are perhaps best seen during the annual Festival in the Desert. This three-day event, held in the middle of the Sahara, includes singing competitions, concerts, camel races, and beauty contests. The festival has rapidly expanded from a local event to an international destination supported by tourism.

The Bambuti is a collective name for four populations native to Central Africa—the Sua, Aka, Efe, and Mbuti. The Bambuti live primarily in the Congo Basin and Ituri Forest. Sometimes, these groups are called “pygmies,” although the term is often considered offensive. Pygmy is a term used to describe various ethnic groups whose average height is unusually low, below 1.5 meters (5 feet).

The Bambuti are believed to have one of the oldest existing bloodlines in the world. Ancient Egyptian records show that the Bambuti have been living in the same area for 4,500 years. Geneticists are interested in the Bambuti for this reason. Many researchers conclude that their ancestors were likely one of the first modern humans to migrate out of Africa.

Bambuti groups are spearheading human rights campaigns aimed at increasing their participation in local and international politics. The Mbuti, for instance, are pressuring the government to include them in the peace process of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Mbuti leaders argue that their people were killed, forced into slavery, and even eaten during the Congo Civil War, which officially ended in 2003. Mbuti leaders have appeared at the United Nations to gather and present testimony on human rights abuses during and after the war. Their efforts led to the presence of U.N. peacekeeping forces in the Ituri Forest.

Political Geography

Africa’s history and development have been shaped by its political geography. Political geography is the internal and external relationships between various governments, citizens, and territories.

Historic Issues

The great kingdoms of West Africa developed between the 9th and 16th centuries. The Kingdom of Ghana (Ghana Empire) became a powerful empire through its gold trade, which reached the rest of Africa and parts of Europe. Ghanaian kings controlled gold-mining operations and implemented a system of taxation that solidified their control of the region for about 400 years.

The Kingdom of Mali (Mali Empire) expanded the Kingdom of Ghana’s trade operations to include trade in salt and copper. The Kingdom of Mali’s great wealth contributed to the creation of learning centers where Muslim scholars from around the world came to study. These centers greatly added to Africa’s cultural and academic enrichment.

The Kingdom of Songhai (Songhai Empire) combined the powerful forces of Islam, commercial trade, and scholarship. Songhai kings expanded trade routes, set up a new system of laws, expanded the military, and encouraged scholarship to unify and stabilize their empire. Their economic and social power was anchored by the Islamic faith.

Colonization dramatically changed Africa. From the 1880s to the 1900s, almost all of Africa was exploited and colonized, a period known as the “Scramble for Africa.” European powers saw Africa as a source of raw materials and a market for manufactured goods. Important European colonizers included Britain, France, Germany, Belgium, and Italy.

The legacy of colonialism haunts Africa today. Colonialism forced environmental, political, social, and religious change to Africa. Natural resources, including diamonds and gold, were over-exploited. European business owners benefitted from trade in these natural resources, while Africans labored in poor conditions without adequate pay.

European powers drew new political borders that divided established governments and cultural groups. These new boundaries also forced different cultural groups to live together. This restructuring process brought out cultural tensions, causing deep ethnic conflict that continues today.

In Africa, Islam and Christianity grew with colonialism. Christianity was spread through the work of European missionaries, while Islam consolidated its power in certain undisturbed regions and urban centers.

World War II (1939-1945) empowered Africans to confront colonial rule. Africans were inspired by their service in the Allies’ forces and by the Allies’ commitment to the rights of self-government. Africans’ belief in the possibility of independence was further supported by the independence of India and Pakistan in 1947. Mahatma Gandhi, an Indian independence leader who began his career in South Africa, said: “I venture to think that the Allied declaration that the Allies are fighting to make the world safe for the freedom of the individual and for democracy sounds hollow so long as India, and for that matter Africa, are exploited by Great Britain.”

By 1966, all but six African countries were independent nation-states. Funding from the Soviet Union and independent African states was integral to the success of Africa’s independence movements. Regions in Africa continue to fight for their political independence. Western Sahara, for instance, has been under Moroccan control since 1979. The United Nations is currently sponsoring talks between Morocco and a Western Sahara rebel group called the Polisario Front, which supports independence.

Contemporary Issues

Managing inter-ethnic conflict continues to be an important factor in maintaining national, regional, and continent-wide security. One of the chief areas of conflict is the struggle between sedentary and nomadic groups over control of resources and land.

The conflict in Sudan’s Darfur region, for example, is between nomadic and sedentary communities who are fighting over water and grazing rights for livestock. The conflict also involves religious, cultural, and economic tensions. In 2003, the Sudan Liberation Army (SLA) and Justice and Equality Movement (JEM), groups from Darfur, attacked government targets in Sudan’s capital, Khartoum.

The SLA and JEM were from different religious and cultural backgrounds than the government of Sudan. The Darfurians were mostly Christians, while the Sudanese government is mostly Muslim. Darfurians are mostly “black” Africans, meaning their cultural identity is from a region south of the Sahara. The Sudanese government is dominated by Arabs, people from North Africa and the Arabian Peninsula. The SLA and JEM were mostly farmers. They claimed their land and grazing rights were consistently being trespassed by nomadic Arab groups.

The Sudanese government responded violently to the attacks by the SLA and JEM. Many international organizations believe the government had a direct relationship with the Arab Janjaweed. The Janjaweed are militias, or independent armed groups. The Janjaweed routinely stole from, kidnapped, killed, and raped Darfurians to force them off their land. The United Nations says up to 300,000 people have died as a result of war, hunger, and disease. More than 2.7 million people have fled their homes to live in insecure and impoverished camps.

The international community’s response to this conflict has been extensive. Thousands of African Union-United Nation peacekeepers remain in the region. Other groups have organized peace talks between government officials and JEM, culminating in a 2009 peace deal signed in Qatar. The International Criminal Court in The Hague has issued an arrest warrant for Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir for war crimes and crimes against humanity.

As a result of ethnic conflicts like the one in Darfur, Africa has more internally displaced people (IDPs) than any other continent. IDPs are people who are forced to flee their home but who, unlike a refugee, remain within their country’s borders. In 2009, there were an estimated 11.6 million IDPs in Africa, representing more than 40 percent of the world’s total IDP population.

Regional and international political bodies have taken important steps in resolving the causes and effects of internal displacement. In October 2009, the African Union adopted the Kampala Convention, recognized as the first agreement in the world to protect the rights of IDPs.

Future Issues

Africa’s most pressing issues can be framed through the United Nations’ Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). All 192 members of the United Nations and at least 23 international organizations have agreed to meet the goals by 2015. These goals are:

1) eradicate extreme poverty and hunger;

2) achieve universal primary education;

3) promote gender equality and empower women;

4) reduce child mortality rates;

5) improve maternal health;

6) combat HIV/AIDS, malaria, and other diseases;

7) ensure environmental sustainability;

8) develop a global partnership for development.

These issues disproportionately affect Africa. Because of this, the international community has focused its attention on the continent.

Many parts of Africa are affected by hunger and extreme poverty. In 2009, 22 of 24 nations identified as having “Low Human Development” on the U.N.’s Human Development Index were located in Sub-Saharan Africa. In many nations, gross domestic product per person is less than $200 per year, with the vast majority of the population living on less than $1 per day.

Africa’s committee for the Millennium Development Goals focuses on three key issues: increasing agricultural productivity, building infrastructure, and creating nutrition and school feeding programs. Key goals include doubling food yields by 2012, halving the proportion of people without access to adequate water supply and sanitation, and providing universal access to critical nutrition.

Scholars, scientists, and politicians believe climate change will negatively affect the economic and social well-being of Africa more than any other continent. Rising temperatures have caused precipitation patterns to change, crops to reach the upper limits of heat tolerance, pastoral farmers to spend more time in search of water supplies, and malaria and other diseases to spread throughout the continent.

International organizations and agreements, such as the Copenhagen Accord, have guaranteed funding for measures to combat or reduce the effects of climate change in Africa. Many African politicians and scholars, however, are critical of this funding. They say it addresses the effects of climate change after they occur, rather than creating programs to prevent global warming, the current period of climate change. African leaders also criticize developed countries for not making more of an internal commitment to reducing carbon emissions. Developed countries, not Africa, are the world’s largest producers of carbon emissions.

What is certain is that Africa will need foreign assistance in order to successfully combat climate change. Leaders within Africa and outside it will need to seek greater international cooperation for this to become a reality.

IMAGE: Abuja, Nigerian capital.