By Olanrewaju Onigegewura

The first time I heard of Ligali Mukaiba was in 1991. I had accompanied Luqman Olániíyí ANÍMÁSHÀUN to Ibadan for the funeral rites of his grandmother in Ayéyé. We decided to visit another mutual friend, Táíwò Kazeem ÀRÁNSÍ-ADÉYÉMO. We met Taiwo’s father, Alhaji Aransi, in his living room. The old man was listening to his gramophone. It could have been His Master’s Voice brand. I am not sure.

I was enthralled by the music playing on the gramophone. Of course, I knew Haruna Bello (later known as Haruna Ishola); Joseph Olatunji from Iseyin (who later became Yusuf Olatunji of Abeokuta); Waidi Ayinla (Ayinla Omowura), Kasumu Adio, S. Aka Omo Lawale, Kawu Aminu, Salami Balogun (Lefty) and others in their generation. But this voice! I had never heard of it! The voice was almost feminine. It was not as fast-paced as Ayinla Omowura and it was not as rhythmic as Haruna Ishola. It was somewhat unique and distinct. The word that came to my mind was ‘unconventional’. I checked the album sleeve. Ligali Mukaiba!

More than 26 years later, I can still hear that faint, almost tremulous voice: “Sékí mo níba lèrín opó, ìwòn lèrín adéléboò…” (A widow’s smile is brief. That of a housewife is modest). Ligali’s selling point was his inimitable voice. A respected music commentator said of his voice: “Almost defying comprehension and definition, his style was unique in all its ramifications.

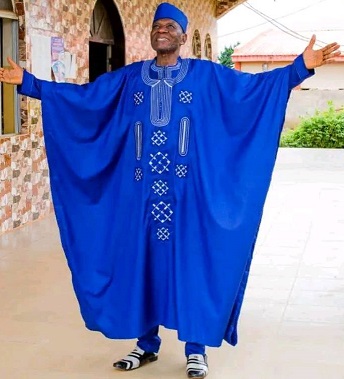

While the others projected their messages with all clarity and intensity, sometime wailing and screaming as in the case of Ayinla Omowura, ‘Baba Lepe’ as he was fondly called, was soft-spoken, yet effective. He sang with a sonorous, falsetto voice comparable to Tunde Nightingale of vintage juju music of owambe type.” Today is the 33rd anniversary of Ligali Mukaiba’s death. He breathed his last on June 22, 1984. From 1945 to 1984, he straddled the music scene in the west coast of Africa like a giant. From his base in Epe (he was fondly called Baba L’Epe), his influence went as far as Northern Nigeria.

Ligali was born on April 5, 1924. His father, Ismail Sanni Mukaiba, was a fisherman. His mother, Sariyu Mukaiba, was a trader. He was a native of Ajagannabe area of Epe. As was customary in those days, Ligali learnt fishing from his father. He later left fishing to become a tailor. (Emi ti ko se telo ri o, ki n to wa d’oga alapala o, mo ti sabere dowo, mo ran danshiki pelu buba, mo ran simi fun madam – (I was formerly a tailor before I became a Master Musician. I have made money from tailoring (needle). I have sewn danshiki and buba for men. I have also sewn for women).

However, notwithstanding that he was a successful tailor, his mind was elsewhere. In 1945, he formed his own apala band. I have not been able to establish whether he was an apprentice musician at any point. He was first signed on to Decca Records. It was with Decca Records that he recorded hits like ‘Late Segun Awolowo’ to console Obafemi Awolowo on the loss of his son; ‘Orin Obinrin’; ‘Omo Jaye-jaye’; and ‘Owo Olowo’, amongst others.

Yoruba music is synonymous with rivalry. Yusuf Olatunji’s archrival was S. Aka Omo Lawale (You may wish to listen to Yesufu Kelani’s 1972 album for a first hand account of their epic battle). Kasumu Adio fought Haruna Ishola till death (In Eni fi ibi su oloore, Kasumu berated Haruna for claiming to have learnt music from no one). Ayinla Omowura took on both Ayinde Barrister and Fatai Olowonyo. Even in the neighbouring Republic of Benin, Yusuf Ishola Oloyede and Surajdou Alabi sent missiles to each other regularly. Ligali Mukaiba was not an exception.

His leading rival was Alabi Elewuro. The duo split Epe community into two. From my researches, I discovered that Eko Epe followed Elewuro and Ijebu Epe adored Ligali Mukaiba. Ligali was however not a local champion. From Epe to Ibadan, to Lagos, to Kaduna, to Ilorin, Ligali had a cult-like following.

He later left Decca Records for Shanu Olu Records. It was with Shanu Olu that his talent as a Master Musician blossomed. He moved from recording on single and extended plays to recording on 33 vinyl. His evergreen albums were recorded under Shanu Olu label.

It is very difficult to classify Ligali Mukaiba. His songs cut across all societal strata. He was a social commentator. He was a philosopher. He was an entertainer. He waxed quite a number of albums on topical social issues. He commemorated Nigeria’s 11th Independence Anniversary in 1971 with Ominira. In the same album, he sang about the completion of the Ikorodu-Epe road. His 1976 album to mark Murtala Muhammed’s assassination remains evergreen more than 41 years after it was released.

Ligali was also a moral crusader. In Bi o kirun kirun, he condemned religion without morality. According to him, endless prayers and ceaseless fasting without being kind to parents is meaningless. In another album, Sina ko dara (Adultery is Condemnable), he educated his listeners on the evils of adultery. He went on to identify 8 groups of people who should never be involved in adultery.

I have not been able to establish this fact but it appears to me that he was ill towards the end of his life. In at least two albums, he sang of recuperating after an illness. In Otito Oro, he sang thus: Won ti so pe iku ki ti eyin pa omo awo, won ti so pe iku ki ti eyin pa adan, ara lo se wéré wéré (They have said that death doesn’t kill a young Ifa devotee, They have said that death doesn’t kill you young bats, it is the body that is weak).

To say that Ligali Mukaiba was a genius was to say the least. Like the proverbial cock, his crow reached both the village and the town. It is a sad commentary and a tragic reflection of our society that we do not celebrate our cultural icons. Our heritage is being eroded by combined forces of western influence and our own misplaced values.

In the words of Benson Idonije, a foremost music critic: “The name of Ligali Mukaiba has gone down as one of the most creative apala exponents on the scene because not only did he evolve rhythms that were delicate, oblivious of the fact, he evolved tempos and rhythms that bordered on unusual time signatures like 5/4 and 7/8. Besides, he sang with a falsetto voice that was wedded in the traditional blues idiom. Ligali Mukaiba’s works deserve to be reissued for this innovation.”

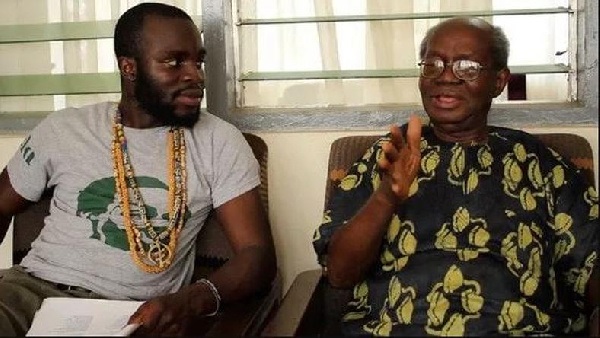

Ligali Mukaiba had four wives: Memunat, Rabiat, Halimot and Rasheedat. He was blessed with 22 children. On a trip to Abeokuta in 2006, I came across a video of Ligali Mukaiba! Shocked. I looked again. It was Ligali’s unmistakable voice of course. But the visual was of those of his children who took it upon themselves to re-invent the legacy of their illustrious father. According to my sources, four of the children of the late maestro are playing one form of music or another.

The question is not whether there will be another Ligali Mukaiba. Ligali was too complex a musician to be copied. His voice was unique. His style was different. The nearest I have seen is Madam Mujidatu Ogunfalu. The question is how do we preserve the legacy of this legend for generations yet unborn!

- Onigegewura, a legal practitioner, is an amateur historian

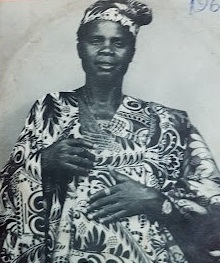

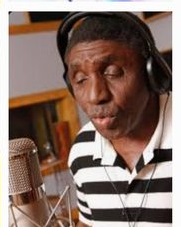

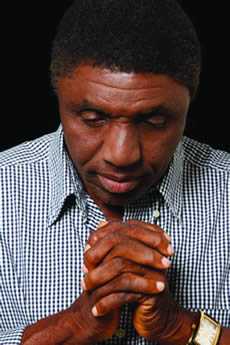

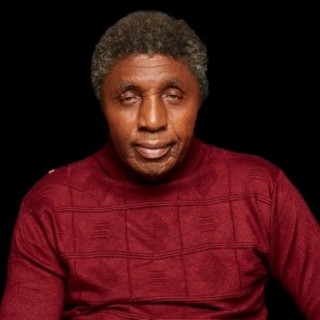

IMAGE: Ligali Mukaiba.